Bannockburn Genetic Genealogy Project

The aim of the project was to combine traditional genealogy, historical context and DNA analysis in order to connect individuals who share the same common ancestor even if one of them has no documentary evidence.

Why use genetic genealogy?

Genetic genealogy can help individuals answer questions which cannot otherwise be answered due to a lack of documentary evidence. It enables each of us to potentially connect to individuals who have a verified documentary descent from historic individuals, for example the men who fought at Bannockburn.

What is genetic genealogy?

Until recently research into the origin of an individual's surname has been limited by several factors: first the survival of documentary sources, and secondly an individual's ancestor actually being recorded within such sources. Fortunately we can now overcome the gaps inherent in documentary records through the use of DNA analysis. Information about our ancestors is preserved in the genetic code we inherit from our parents and holds the key to discovering relationships and origins beyond the reach of traditional research. Due to its special properties and unique path of inheritance DNA can therefore help us retrace the steps of some of these ancestors in much greater depth.

The genetic code in our DNA is passed down the generations, but every so often in the process of copying six billion letters of code, errors occur. These copy errors are called mutations. Scientists have calculated how often these mutations are expected to occur by a technique called the molecular clock. This enables them to be dated. The interpretation process involves comparing the differences identified between individuals to establish the degree of relatedness they share (the genetic distance). Genetic genealogy uses traditional documentary evidence and DNA results from individuals who are alive today. We do not dig up old bones or raid graveyards!

Surnames

Exploring the origin and meaning of surnames has been a popular pursuit since the Victorian era when the classification and recording of their history laid the foundation for the information within many of the books on the subject we read today. However it is apparent from recent research that although some names may have a common, even singular origin, others have been created on multiple occasions at different times and in different locations.

Surnames in the British Isles were adopted and become inherited from father to son between the 12th and 16th centuries. As communities grew in size and became more complex, individuals were required to be identified by a fixed name particularly due to the importance of the transfer of land and property. However in a few areas fixed surnames were adopted after the 16th century. For a variety of reasons not all individuals who have the same name share the same common ancestor who first carried the name. Because not all name bearers of a specific surname share the ancestor who originally adopted that name, the history attached to a name in a particular area need not be the actual paternal history of all men who carry that surname today.

Some of the more common reasons for a change of surname remain hidden to the holder until they begin tracing their ancestry and uncover documentary evidence or take a Y-DNA test and find they do not match other men who share their surname. This might be because of illegitimacy or adoption whether formally or informally. Other reasons for change of surname can include: personal choice – an individual may have changed their surname, e.g. to hide racial origins or cover up their past; inheritance - tenants of a large landowner would take his name as their feudal superior who would provide in exchange protection and access to material benefits; men who married a female heir of a land owning family would upon marriage change their surname for the purpose of inheritance. In summary, bearing a popular surname is no guarantee that an individual is descended paternally from the individual who first adopted the name or from landed families bearing that name.

Documentary evidence

Family history and genealogy research depends on identifying documents and records which contain information on our ancestors. Birth, marriage and death records can easily take us back to the mid-19th century and for many individuals church records will allow the family tree to be traced back to the 1780s in Scotland when many parish records begin to fade away. If you are fortunate and your ancestors owned property it may well be possible to trace back another 150 years, but for the vast majority of us this is not possible. What next?

Why DNA testing is important

DNA testing can be used to overcome gaps or dead ends in the paper trail and show connections at the period of surname formation and their adoption around 1200-1600 AD. It can therefore help men identify the history of their paternal lineage and show the inter-relatedness of different clans, families and surnames.

How does DNA testing work?

Almost every cell in your body contains DNA. It is your individual ancestral barcode, linking you back to the very beginnings of life on Earth. Although your DNA is inherited half from your mother and half from your father there are two particular types of DNA that are uniquely transmitted by one or other parent and whether you inherit one or both of these depends on your sex.

Mitochondrial DNA is found in every cell in the body and inherited by both males and females alike from their mother who inherited it from her mother and so on. As mitochondrial DNA is only inherited from a person's mother, it does not follow the male line so is not useful to trace the descent of males or surnames and has not been used in this study.

Y-chromosome testing (Y-DNA)

The Y-chromosome is one of the two sex chromosomes (the other is the x-chromosome) and is inherited by boys from their father who inherit it from their father and so forth back into the mist of time. Women do not have a Y chromosome having instead two X chromosomes (men have an X and a Y). It is the Y-chromosome which has been used in this study. The Y-chromosome is located in the cell's nucleus. As surnames typically follow the paternal line in the British Isles, Y-DNA can be used to establish whether men share a common male ancestor. The image below illustrates the path of the Y-chromosome down the generations from father to son, to grandson and so forth.

How is the DNA collected?

Cells are collected from the mouth by means of a simple mouth swab. The swab is rubbed over the cheek wall for a minute to pick up cells. The samples were then sent to Family Tree DNA in Houston for processing and matching.

Processing and analysis

DNA was extracted from cells in the sample and then processed to identify the unique results for each individual in the Project. The results were then compared to those from other individuals in the Family Tree DNA database which has over half a million Y-DNA samples. The British Isles are heavily represented in the database and in particular Scottish clans and families.

Case studies

Rigorous investigation of traditional genealogies and contemporary documentation from the period of the Battle identified a number of lineages which had an unbroken male line stretching from participants in the Battle in 1314 to the present day. Unfortunately gaps in documentation and the failure of male line descendants ruled out many families who were present at the battle. Initially, four families were researched: descending from Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland; Angus 'Og' MacDonald of the Isles; Thomas de Berkeley, 1st Lord Berkeley; and Sir Thomas de Gray. Individual living male descendants were invited to take a Y-chromosome DNA test with Family Tree DNA, the project's testing company. Test results for the latter two English families were deemed inconclusive so are not presented in the Project results.

Stewart

Clan Donald

The Stewart and MacDonald surnames are very well represented in the Family Tree DNA database. The Clan Donald DNA Project is the largest surname project in the world with over 1500 participants while the Stewart/Stuart DNA Project has 800 participants. Both these projects have extensively tested individuals who are known descendants of the chiefly or cadet lines or other well documented branches of each clan. The test results for participants Stewart and MacDonald were compared with other closely matching individuals in the database and analysis indicated that their common ancestors were more recent than 1314. The two Stewart participants, the Earl Castle Stewart and his close match Mr Paul Thompson, also took an advanced DNA test to confirm whether they belonged to the Albany Stewarts or to the Stewarts of Bonkyl.

A known descendant of the Kinlochmoidart family, a branch of the MacDonalds of Clanranald and a direct descendant of Angus Og of the Isles, matched Mr Lee MacDonald who also undertook advanced testing for SNP branch markers. This confirmed that they both shared descent from Angus 'Og' of the Isles.

DNA changes over time

Over time, DNA accumulates changes, usually caused by cosmic rays and other environmental factors. It is known with some accuracy how often that happens. Therefore, it is possible to say how closely or how distantly related two individuals are by how similar or dissimilar is their DNA. This is the basis of genetic genealogy testing. By comparing DNA test results from two or more people and measuring the differences in the results an estimate can be made of how many generations in the past they shared a common male ancestor.

DNA tests used for the project

DNA testing for surname research uses two different types of test. The first, an STR test, gives matching results with men in the last four or five hundred years, while the second, a SNP test, is used for defining branching within lineages and placement of the testers on the Y-DNA phylogenetic tree.

STR markers and SNP markers

STRs (short tandem repeats) measure the number of times a sequence of genetic code is repeated at a specific location on the Y-chromosome. Common tests available are on 37, 67 or 111 markers. The values for these marker positions can change over time due to errors when the DNA code is being copied between generations. The mutation rate for these changes (mutations) can be measured by what is known as the molecular clock. Algorithms within the matching database also provide the probable time to a shared common ancestor. This is the type of test recommended for establishing connections in the last four to five hundred years for genealogical purposes.

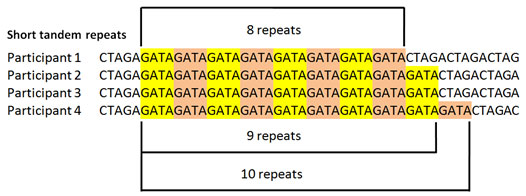

The genetic code is made up of four base molecules (nucleotides) adenine, guanine, thymine and cytosine (A, G, T, C). If the sequence GATA is repeated 3 times GATAGATAGATA at a certain position on the Y-chromosome then the DNA result for that marker position is 3. In the example below the results from testing of four participants is shown at just one marker position on the Y-chromosome. Participant 1 has eight repeats of the sequence; participants 2 and 3 have nine repeats while participant 4 has ten repeats.

Fig 3. Short Tandem Repeats (STR)

For the Project, participants tested either 67 or 111 marker positions and the number of differences was then measured between their closest matches.

The Earl Castle Stewart is the direct descendant of Walter Stewart 6th High Steward of Scotland (ca 1296 – 1327) a leading participant at the Battle of Bannockburn. The Earl is the 21st generation since Walter Stewart. He tested 111 STR markers with Family Tree DNA. His closest match was Paul Thompson from Gloucestershire. It was clear from Paul's many close DNA matches to men with the surname of Stewart that his family's surname had changed and he is in fact a member of the Stewart family. His earliest traceable ancestor with the Thompson surname is William Thompson born around 1739 who was a sailmaker, chandler and ship victualler in Liverpool where he died in 1813.

Earl Castle Stewart and Paul Thompson share 6 differences out of 111 STR markers tested. Two models were used to establish the time frame to their shared common ancestor.

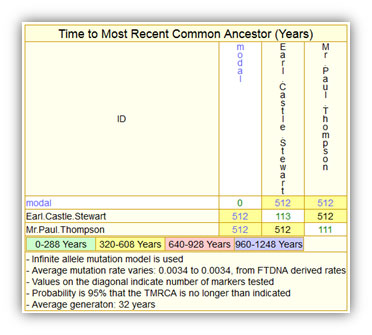

Dean McGee Utility - The time to their shared common ancestor was calculated as not more than 512 years ago at a 95% confidence level (probability) using 32 years per generation (700 years divided by 21 generations), Family Tree DNA mutation rates and the Infinite Allele Mutation Model. Their common Stewart ancestor could have lived sometime after 1502 AD.

Fig 4. Time to most recent common ancestor between Earl Castle Stewart and Paul Thompson.

Table produced by Dean McGee Y-DNA Comparison Utility.

The second model used was that provided by the testing company Family Tree DNA. A difference of 6 over 111 markers indicated that a shared common ancestor was not more than 17 generations ago at a 95% confidence level (probability). This can be extrapolated as no more than 544 years ago (1470 AD).

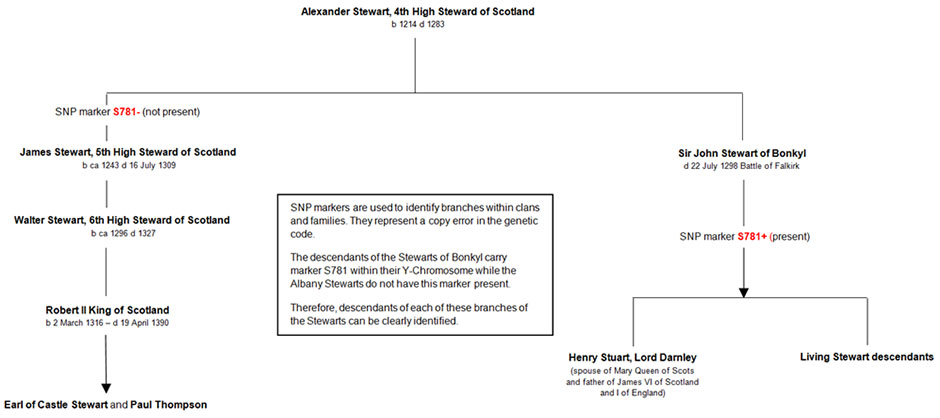

The Stewart family is divided into two different branches depending on whether they are descendants of James Stewart, 5th High Stewart of Scotland (b ca 1243 – d 1309) or his brother Sir John Stewart of Bonkyl who died at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298. STR markers cannot differentiate between the different branches of the Stewarts at a distance of 700 years, however SNP markers can.

SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) are markers which identify a copy error on just one base molecule in the DNA sequence. For example base guanine (G) mutating to base adenine (A). SNP markers are like permanent signposts in the DNA sequence and can be used to identify different branches of male line descendants which separated more than 500 years ago.

Descendants of Sir John Stewart of Bonkyl are known to carry a SNP mutation at a specific position on the Y-chromosome which has been called marker S781. Another participant in the Project, a man named Fred Stewart, also tested for marker S781 and was found to be 'positive' meaning he carried the marker and so could not be a descendant of Walter Stewart 6th High Steward of Scotland. The result confirmed that Fred was in fact a descendant of Sir John Stewart of Bonkyl. When Earl Castle Stewart and Paul Thompson tested for this marker (S781) they were found to not carry it, in other words they were deemed 'negative' for this marker.

Participant name |

Y chromosome |

Reference |

Mutation |

Result |

SNP no. S781 |

Stewart branch |

Fred Stewart |

18538470 |

G |

A |

Positive |

S781+ |

Bonkyl |

Earl Castle Stewart |

18538470 |

G |

G |

Negative |

S781- |

Albany |

Paul Thompson |

18538470 |

G |

G |

Negative |

S781- |

Albany |

Results

The chart below illustrates in graphical form the descent of the Earl Castle Stewart and Paul Thompson from the Albany High Stewards who are negative for marker S781 and the descendants of Sir John Stewart of Bonkyl, from whom Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley spouse of Mary Queen of Scots descends, who are positive for marker S781+.

See the full Genetic Genealogy Trees

Stewart conclusion

The results from both types of test conclusively confirm that Paul Thompson is a descendant of Walter Stewart 6th High Steward of Scotland who fought at Bannockburn. At some point one of his ancestors adopted the Thompson surname, nevertheless his Y-chromosome confirms his direct paternal descent from the Albany Stewarts.

Descendants of Angus 'Og' of the Isles

The Clan MacDonald chiefs all descend from Angus Og who was the grandson of Donald who gave his name to the MacDonald clan. Angus Og brought a large force of warriors to fight at Bannockburn from the Western Isles and Argyllshire where he was Lord. The Clan Donald chiefs were one of the first clans to take DNA tests back in the year 2003 which revealed that they all shared a common paternal ancestor. One of the chiefs who tested in that early study was Ranald A. MacDonald, Captain and Chief of Clanranald. All the chiefs later retested with Family Tree DNA based in Houston which hosts the Clan Donald DNA Project.

Clanranald's closest DNA match is with Lee MacDonald who lives in Canada. Lee's earliest known ancestor was Ward McDonald who was born circa 1792 in Ireland. Ward emigrated to Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1816 and then moved on to New Brunswick in Canada where he was a merchant. Nothing is known about his parents or likely siblings or from which branch of the Clan Donald he descends. Lee had taken a 67 STR marker test in the hope of establishing where his ancestor had come from before emigrating.

Lee MacDonald and Ranald MacDonald of Clanranald have only 2 differences out of 67 STR markers tested.

The STR DNA test suggests a common ancestor was shared between Lee MacDonald and Clanranald at over 95% confidence level (probability) of not more than 12 generations ago - circa 1530 AD.

Lee MacDonald also took an advanced test which analysed many thousands of SNP markers to establish which branch of Clan Donald he belonged to. The results of this 'Big-Y' test confirmed he is a descendant of the MacDonalds of Clanranald. Therefore Lee MacDonald like Ranald A. MacDonald, Captain and Chief of Clanranald is a direct descendant of Angus Og of the Isles who fought at Bannockburn.

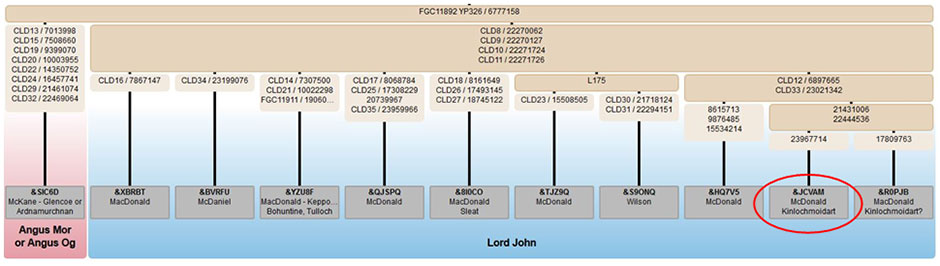

Dr Doug McDonald, administrator of the Clan Donald DNA Project, has been instrumental in discovering new SNP branch markers specific to the MacDonalds. Results from the Big-Y test available from Family Tree DNA have identified a mutation (FGC11892) believed to have occurred around 1230-1300 AD (top line of chart below). Immediately below in the second box are new markers CLD8, CLD9, CLD10 and CLD11 believed to have occurred in John, first Lord of the Isles, who died in 1386. These mutations are carried by Lee MacDonald who is located second in from the right (red circle) in the chart. Lee shares two mutations with another individual who is from the Kinlochmoidart branch of Clanranald (21431006, 22444536). The Kinlochmoidart family are descended from John, fifth son of Allan, 9th of Clanranald.

Fig 6. Branching within the Clan Donald DNA Project revealed by SNP testing. Courtesy of Dr Doug McDonald.

Clan Donald conclusion

The results from both types of test have conclusively revealed that Lee MacDonald is a descendant of Angus 'Og' of the Isles who fought at Bannockburn despite having no documented ancestors before the late eighteenth century. They also confirm that he belongs to the Kinlochmoidart branch of Clanranald.

The future - how you can take part

How can you get involved? - Any male can take a Y-DNA test to investigate their paternal ancestry. We would recommend taking either a 37 or 67 STR marker test and to join your relevant clan, family or surname project hosted at Family Tree DNA or other provider. If you are female, you need to get a male relative such as a father, brother, uncle or nephew who bears the surname of interest to take a Y-DNA test on your behalf, though other DNA tests are available to women.

Useful links

Clan Donald DNA Project http://dna-project.clan-donald-usa.org/

Stewart / Stuart DNA Project http://www.familytreedna.com/public/Stewart/

Scottish DNA Project http://scottishdna.wordpress.com/

Dean McGee Y-Utility: Y-DNA Comparison Utility, FTDNA 111 http://www.mymcgee.com/tools/yutility111.html

Acknowledgements (Bannockburn Genetic Genealogy Project)

Arthur Patrick Avondale Stuart, 8th Earl of Castle Stewart

Paul John Thompson

Ranald Alexander MacDonald of Clanranald, 24th Captain and Chief of Clanranald

Lee Weldon MacDonald and Elizabeth Bennett

Belinda Dettmann and Kathi Bobb, Stewart Stuart DNA Project

Dr Doug McDonald, Clan Donald DNA Project

Max Blankfeld, Family Tree DNA

June Willing

A special thank you to the University of Strathclyde for providing this information.